Gussan wants to capture nature’s patterns, learn Arabic, and never stop asking big questions.

Gussan Jalil is a photographer and recent UNT graduate who spent a semester at xREZ Art + Science Lab to experiment with an art form in which he electrocutes 4×5 film in order to capture the patterns electricity makes in the film’s emulsion.

He says taking courses at xREZ allowed him the freedom to treat his art like a science and complete a project in which he learned that asking more and more questions can be good fuel for more interesting inquiry.

News@xREZ talked with Gus and learned he plans to travel to Jordan to experience the art of a different land and the culture of his Palestinian heritage, working to carve a path toward his dream job, making the art he has yet to discover.

Gussan Jalil is geared for international travel and exploration.

Amelia Jaycen: So Gus, how did you hear about xREZ Art + Science lab?

Gussan Jalil: I heard about xREZ through my photography professor Dornith Doherty and my friend Jacob Mitchell who works here. And I think because some of my work in photography was a little bit “out there,” I got a lot of advice to go more toward a new media degree than photography, but I never wanted to go that route.

A: Why weren’t you interested in a new media degree?

G: Well, because I love film, and I love photography. I feel like that’s my calling.

A: So tell me about some of the photographic work you’ve done at UNT.

G: I first started documenting cymatics, which is the effect of vibrations through a medium. I created a series of work where I photographed the results of frequencies generated with an amplifier and a synthesizer. I also downloaded a tone generator app on my phone, and I put a rubber balloon around a small speaker with a drop of water on it. I also made a short demonstration video, so viewers could see the work that I had photographed, visualize how it was created through the video and then also manipulate it themselves. So that project got me into the program. There were a lot of influences, people telling me that my work was super new media. But I was just really always interested in the photographic process and the materials. Some of my other projects have dealt with anything from coping with stress to playing with water and ice.

A: Tell me about the stress project? How can you capture stress in a photograph?

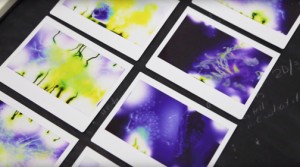

Jalil’s senior exhibit featuring digital prints of scanned 4×5 negatives that were electrocuted using a Van de Graaff generator.

G: Well I had been going through a lot of stuff my junior year: my brother was hospitalized, my sister and her husband weren’t doing so well. So I had a world of family stress going on top of my school work. But that doesn’t really photograph well, it’s hard to convey that tableau.

A: So how did that end up showing in your work?

G: I was just photographing a lot, staying up really late at night and trying to find interesting places to sneak into and try to photograph in that setting. I photographed once in the Eagle Commons Library, which had an empty basement where all the books were cleared and it was just empty bookshelves. It felt like a right setting to shoot because I thought, this is kind of how I feel: I’m in this setting with all these empty bookshelves when the purpose of this place is to fill knowledge. But what is knowledge anyway? A lot of my work is about generally asking questions, not at all trying to answer them. And I was always really thankful to have Professor West there to let me experiment with what I wanted to do, to make what I wanted to make. It was awesome.

A: Is it different from other places or other ways you’ve worked to feel that you could experiment?

G: I’ve gotten that general feeling from upper level studio classes where we were given free reign to experiment and do what we want. But in my class @ xREZ, I didn’t feel like I was forced with any stipulations, and that made it easy for me to free up some stress. In photography courses there are requirements such as that I have to have 15 photographs, and I have to have them all in this perfect, documented style, and it has to be in this particular box. None of that came through in my independent study at xREZ. Here, it was my goals, and I put forth the effort to complete tasks A, B, and C to get to D. So I never had full-ranging freedom before, and it was really awesome. I wish I had gotten in earlier to do an independent study like that where from the beginning there is that freedom.

A: So how does the role of research factor into your work as an artist? I had a hypothesis, I experimented, and I came to a conclusion. My research question was what are the differences, if any, in how light-sensitive film will react to electricity? And my variables were color, electricity, and sensitivity of the film.

G: I think it’s important, like that old saying, “If you don’t study history, you’re bound to repeat it.” That factors into many facets of life. I think it’s definitely important to know what you’re doing and what type of message you’re trying to send, as well as what the work is representing. A general understanding of your work requires you to do research, to learn what others have done. So I think it’s heavily important, I just think that if you don’t know how to talk about your work, then you’re not working on it. And I’ve seen that in a lot of classes, art work that made me think, “Wow, this work is beautiful. But do you understand the things that you’re touching down on? Do you understand why you’re doing it?” I feel like UNT artists are heavily conceptual. If your mark on paper means something to you, and as long as that meaning is conveyed in the work or you reach out, and you’re trying to make that come through, then that’s art-making. I feel like intent is as much as content, if not more.

A: So tell me about the development of these electricity photographs you’re making. Did that come together just this semester or was that longer in the making?

G: I came across that project or that process at the end of my junior year, so it was right after I had been stressing about all this stuff that was going on in my life. I read of this artist named Hiroshi Sugimoto who I have taken a lot of influence from. I wanted to emulate that same notion of importance he brings. So I figured out that I wanted to manipulate my photographs with electricity. Then I got in contact with my old chemistry teacher from high school, and he allowed me to set everything up to try it. He had a back closet that I brought his Van de Graaff generator in to use. There were some occasions where somebody would walk in, and I was in there going, “No, no, no, no, no!” because I was in complete darkness exposing the film on the Van de Graaff machine.

So that was the first set of experiments I did, and I brought it back here and processed it, scanned the images, and I got great responses. I was just doing black and white film at that time, but my instructor really enjoyed the images. It was a very nice padding to the end of that semester. I felt like this work was a base for something bigger. Even at that point I don’t think I really fully knew how I wanted to talk about my work. I was experimenting with a process for which I didn’t yet have the materials or equipment. I was making these visceral images, and I didn’t know what I was looking at entirely. It takes a while to fully understand how to talk about your work.

That’s what was great about this semester’s course was having all the materials and the equipment and going through that process where I’m electrocuting pieces of gelatin in darkness. In that process, I definitely had to sit down and think about how I wanted to address what I was working on.

Jalil called his electrocuted images Lichtenberg experiments after the name for the branching, vein-like design electricity makes in most mediums, whether skin, wood, metal or film.

A: So have you come to a conclusion about the meaning of these electrocuted film images?

G: Yeah, I know that I’m looking at these images and making these experiments and trying to find relatable forms. I’m imitating nature, which is what all art is in some way. My work is trying to capture what is unseen but oddly familiar. Because I see it everywhere, this electrical pattern, and I’m interested in why that pattern forms, asking myself why I am drawing these things together. I’m really just asking questions. That’s what my work has developed into – as if the more questions I ask, and the more I try to investigate those questions, I end up with more questions, and it keeps going. Why is this happening? What is following what? Are the structures of nature following electricity or does the chaotic nature of electricity follow the organic structures of art? I don’t know. I have a lot of experimentation to do, but I don’t think it’s going to yield any kind of tangible answer per se. I’m not looking for answers. I’m just asking a lot of questions that are interesting to me.

A: What you said about constantly generating more questions – that reminds me of my study of science communication. We like to think of science as this practice that is supposed to give answers, definitive answers, but then there’s also a lot of uncertainty, and every study you do brings up more questions. Does your practice creating these images remind you of a scientific study of any kind?

G: Yeah, of course. I definitely approached my work this semester in a scientific way. I posed a question, and I experimented, and I had a hypothesis, and I came to a conclusion. My research question was what are the differences, if any, in how light-sensitive film will react to electricity? And my variables were color, electricity, and sensitivity of the film. So I definitely do think of my work as scientific exploration of the materials of photography.

A: Do you plan to continue this work?

G: I intend to do a lot more studies about different film types and the way that they react. Not just different sensitivities but different brands and the chemical makeup of the actual emulsion as well. So it’s a study that definitely does have more room to grow. I have a lot more variables to test. And I don’t just want to stop at sensitivity. I have a lot of questions about how the film would react indirectly through various materials, organic materials and inorganic materials. I’m deeply interested in electricity and the way it is recorded on the film, whether that be directly or indirectly. It’s so interesting that the material – electricity – that I’m using to comprehend the photographic emulsion material has an intermediary relationship. Electricity is inside us, it’s inside me. That’s just interesting to me to ask, how does that all work?

A: And for this project you bought your own Van de Graaff machine? Where did you get it?

G: Yes I have my own now. I purchased it online from a science classroom website. But it has no other real purpose other than to demonstrate plasma or electricity.

A: Do you know much about the history of the use of that machine? Are the structures of nature following electricity or does the chaotic nature of electricity follow the organic structures of art?

G: It was developed by Robert J. Van de Graaff in the 1920s. It’s not a new technology. It’s a pretty old scientific machine. There have been lots of other generators after that. Tesla and others who have experimented with electricity machines.

A: Are there any other kinds of machines you could have used?

G: I could have used other types or I probably could have made my own. It’s just a belt that’s charging up positive electrons in an insulated bulb. So I could have used a coke can and paperclips, but I wanted something that was going to be consistent and stable and a bit more prestigious. So I finally decided to buckle down and just buy one because it’s what I’m interested in and what I want to experiment with, and I didn’t want to have someone saying “don’t do that.” So I started doing a lot of my work at home in my own bathroom.

A: What are your thoughts on the combination of art + science? Obviously in your project scientific ideas fed your work. Do you think that combination is valuable for other people to pursue?

G: Yeah. I mean I feel like it’s valuable if your work generates a conversation and gets people to ask questions. That’s what art is, and that’s also what science is. They’re kind of two and the same, two peas in a pod. That’s what I’ve found. Especially with photography, it’s always been a science to me, even in the materials. Roland Barthes makes an interesting statement about photographers as agents of death – that’s what he claimed photographers to be. To him they were the people who were solidifying death, the death of the moment. I mean that’s one of man’s greatest wonders is what happens after we die. It’s human to ask questions about death.

A: What is it like to be in the dark working with electricity?

A: What is it like to be in the dark working with electricity?

G: I would turn off all the lights and sit down for 15 minutes and let my eyes adjust, and then get to work finding out where any light was coming into the room. It’s really interesting when you find yourself in a completely dark environment, it’s so abnormal. I think that’s why I’ve always really liked it. You forget, in complete darkness you can raise your hand in front of your face, you can feel it, know it’s there, almost see it but you can’t really. Developing tactile sense is interesting. I like working in the dark.

A: Yeah, I loved darkroom days. I always had a good feeling when I left the darkroom, like I’d been meditating or something. So did all the thunder and lightning storms this spring affect how you were thinking about your work?

G: Of course! The past three weeks I’ve stayed up every night that it stormed, and I have been working on my stuff. So I get to experience my work and this form of energy on the micro scale, and then also so catastrophically on the macro scale, so that was cool. I couldn’t sleep.

A: I can imagine! So congratulations on graduating this spring. What are your plans going forward?

G: Thank you. I am going to try to save up some money, and I’m also going to dedicate at least 2-3 hours a day learning Arabic, trying to get down some of the salutations and greetings, the essential stuff, and then go with my dad to Jordan. He’ll probably stay for two weeks, and then he’s going to leave, and it will just be me there for four to six months.

A: What a neat trip! Are you from Jordan? It’s valuable if your work generates a conversation and gets people to ask questions. That’s what art is, and that’s also what science is.

G: My father is Palestinian. I’m really excited. It’s definitely going to be an experience. It’s something that my brother did when he was 18 and my sister did too. And I’m the first to graduate from college, so it’s my turn now. I’m 22, I graduated, and I have all these routes and options – I have a pretty versatile degree. Our profession allows us to go and do and see what we want. So that’s what I want to do. I plan to go over there, build-up my CV and to hopefully get in with the art scene, if there is an art scene there. Or maybe I will document something about the art world there, if there isn’t one or if there is, see what it’s like. I’m interested to see what kind of hoops that people have to jump through to get their work on the wall, or their message sent, or their film screened. What’s it like there? What’s their process?

A: How has your work @xREZ Lab this semester changed your view on what you can and can’t do? Or your future plans?

G: Well getting to do a couple independent studies with Professor West really sped up the process of graduating this semester. It definitely increased my workload quite a bit, but it also allowed me to strive to finish. I thought to myself, “I can do this. I’ve got 18 hours, and I can complete them all, and then I can go do this trip to Jordan this summer.” So it was something to strive for. Everything that I’ve gone through in my studies in photography, all the critiques, it’s been great, it’s helped me grow, and now I’m ready to be out. Working in the lab also definitely opened up my eyes as to how powerful grant writing can be. Professor West is definitely a steeple of that kind of notion.

A: Have you talked with her about how best to get funding?

Gussan’s “Cleanse Cap Pro” prototype lets the photographer think more about the shot and less about dust.

G: I went to her GET FUNDED! grant writing workshop last semester. And yeah, that’s incredible, I don’t know how she does it, but apparently she does it really well.

A: Tell me about your other independent study with the lens cap.

G: I had come up with that idea a long time ago, and I have been sitting on it. I haven’t really been in the right environment or offered the right amenities to do that. And this semester took a business management and entrepreneurship class, and it really opened my eyes to the process of writing a mission and vision statement and getting everything you need in order to start a company. But I don’t at all intend to jump into the market just yet, I think I need to develop a patent with all of the stipulations and then hold onto that for however long it takes to develop something that I could potentially market to investors, and then get funding for that.

A: So it is a lens cap that keeps your lens clean?

G: Yeah, it’s still in the prototype phase, but it is a lens cap that will double as a lens cleaner, so it will effectively reduce the time that it takes you to get ready to take your shot. It’s still in development where I might need to figure out more how to get that to work. So it is still a work in progress, but I feel like having all the amenities in the Lab has definitely helped bring that idea into a tangible thing.

A: Was that idea the impetus for you taking a business class?

G: I was interested in entrepreneurship. I’ve always enjoyed making things with my hands, especially utilitarian things as far as like other interests go with business and routes I could take. I’ve always been good with crafting things.

A: So if you could have it your way and the world was yours, what would you be doing? What is your dream job?

G: It’s hard to think beyond the expected chain of responsibility: go to college, get a degree, get a job, pay your debt. But my dream job would be just making art. That’s my dream, that’s what I’m pursuing. I would like to be able to travel and share my artwork and get paid for that. I feel like I have to make my own dream job.

A: Like it may not be something that exists?

G: Yeah, it may not be something that’s out there. I’ll have to find it.

A: Good luck out there Gus. I hope you find your dream!

About Gussan

Major: Fine Art Photography

Dream Job: Art + Travel

Hobbies: Cinematography + Storytelling + Stained Glass

Fun Fact: Gus was born to a Palestinian silk and stallion smuggler who settled in Dallas, Texas.

Check out Gus’ Lichtenberg experiments @xREZ

News@xREZ Oct. 29, 2015